... ...

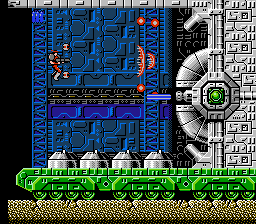

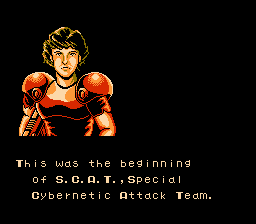

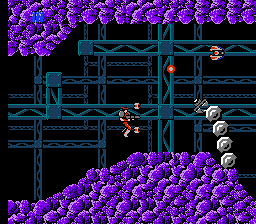

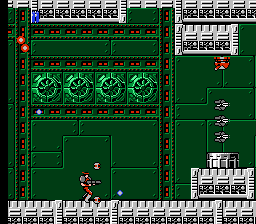

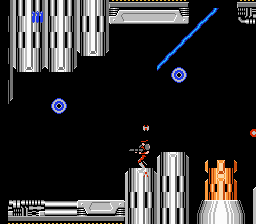

If Contra automatically scrolled and the characters surmounted enemies and obstacles not by jumping, but by moving them around the screen with the D-pad, you might end up with something like Natsume's S.C.A.T. If that doesn't sound like the best idea in the world to you, that's probably because it isn't. S.C.A.T., which stands for "Special Cybernetic Attack Team", has you playing as a man (or woman) who constantly moves in one direction, but can turn around and fire in the other. This differs from most space shooters in which you control a spaceship that can only ever fire in the direction it's moving. It might seem like an innovation, but it comes at the cost of being intuitive.

... ...

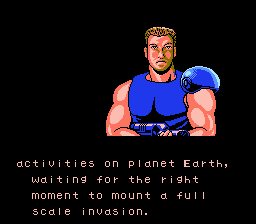

The premise of S.C.A.T. is a typical "aliens have invaded Earth" scenario in which you can choose to be either Arnold Schwarzenegger or Sigourney Weaver. No, I'm neither making that up nor exaggerating. The characters are called "Arnold" and "Sigourney", and their portraits look exactly like their actor counterparts. It's no secret that Predator and Aliens influenced a lot of NES games, and yet I'm still taken aback by this level of transparency.

Of interest to note is that the Japanese version of the game, called Final Mission, has a completely different opening cinema that actually shows the alien invasion and consequent destruction, while the American and European versions opt to alternate between running legs and a conga line of cyborg soldiers sent to fight the aliens. So, in effect, the English and Japanese versions each only have one-half of the opening story. Thankfully, it's not that important, and easy enough to fill in the blanks via the context of the game itself, though it probably accounts for the nonsensical nature of the ending.

... ...

Further investigation reveals that this is far from the only change that was made between the two versions. Along with the European counterpart, Action in New York, which is identical in most respects to S.C.A.T., the alterations were intended to create a much easier experience for English-speaking audiences. I don't think trying to make the game a little more accessible was a completely misguided venture, considering some issues I'll get to in the paragraphs ahead, but Natsume's effort was entirely overzealous. To give a rundown of the changes:

The characters start with six life meter blocks in the English versions; only three in the Japanese game.

Life-restoring powerups were added to the stages in the English versions. No such item existed in Final Mission.

Taking a hit in the Japanese game causes you to lose your special weapon (if you had one collected) and revert to the standard gun. In the English versions, you only lose your special weapon upon a Game Over.

Other than the Laser special weapon, there is no autofire in the Japanese version. (I am not particularly bothered by this change since having autofire leads to less hammering on the button, and thus less wear on your controller and thumb.)

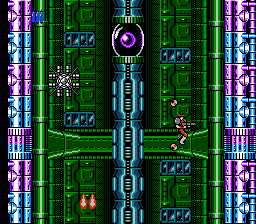

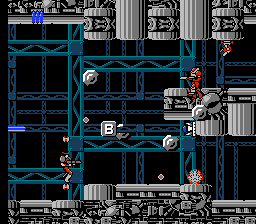

In what is probably the most baffling revision, the two options that surround the characters move with your movement in the Japanese version, but perpetually move back and forth in an arc in the English versions. They can be fixed in place with the A button on both versions, but this system actually feels more awkward in the US/Euro release.

... ...

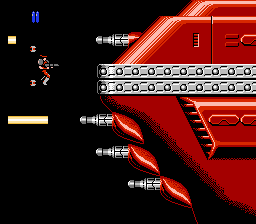

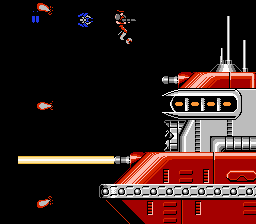

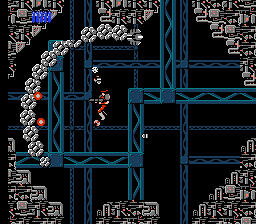

The third and fourth levels have been flipped on the English versions. In Final Mission, the third stage is a battleship in the same vein as Level 3 of R-Type, in which the spaceship boss is so big that it comprises the entire stage. The fourth level is a vertical elevator shaft that scrolls at breakneck speed. It makes more sense, from a narrative standpoint, to reverse these two stages as the English versions imply that the elevator is used to propel the characters into outer space where they eventually confront the battleship.

However, they weren't just swapped - the elevator was significantly toned down in difficulty, as all the wall-walking turrets were removed and some enemies were made less aggressive. (Strangely enough, a part where two large turrets circle the screen that consistently gives me the most trouble was left intact.) This is the only level that had any actual stage elements altered, and the effect is to render what was one of the longest and most difficult parts of Final Mission almost inconsequential.

The changes greatly affect the game's dynamics. Playing Final Mission is a sobering revelation that the first two levels were not meant to be throwaway set pieces and were designed with the penalties in mind. What's even more baffling about this situation is that the bosses were made harder on the US/Euro releases, taking roughly twice as long to kill. I suppose this was done to rebalance the game for the two-player mode, but considering everything else...really, why??

... ...

Despite the level of overkill, the battleship stage and the final stage should still provide a challenge to most players, as it took me a few days of practice to surpass both. Like many shooters of S.C.A.T.'s type that emphasize stage design over bullet saturation, they require a lot of memorization of where obstacles and enemies appear. Both stages have turrets that fire screen-dividing laser beams that you'll want to know ahead of time where they appear so you can maneuver into the "safety zones".

What really creates their challenge is their sheer length and complete lack of any checkpoints. They are some of the longest levels I've ever seen in a shooter. Getting through them, even with a full six life bars, is harrowing, and dying means you have to start the stage all over from the beginning, no matter how far you had gotten. It is very easy to end up just a little bit past where you last progressed, only to be wiped out by the next challenge because you weren't ready for it (which is usually the case with the bosses). Now, consider that the Japanese version only gives you three life blocks and has a considerably harder elevator stage, which is also exceptionally long, and you have a game that many players might not consider finishing if not for the modern advent of save states.

My solution to this problem would not have been to dumb down the game as much as Natsume did. I would say placing reasonable checkpoints in the longest stages would've sufficed. Another possibility would have been to keep S.C.A.T. the way it is for the novice/casual player, but to have included Final Mission as a second quest. When I beat S.C.A.T., I felt almost no compulsion to replay it, and probably wouldn't have bothered if not for the doorway to the Japanese version that emulation provided me.

... ...

The problem in playing as a human instead of a spaceship in a game of this sort is that it's much more difficult to manipulate a vertically-shaped object in and around bullets and other obstacles. The character's ability to face both ways and only fire in the direction he/she is facing creates further complications. While the option for destroying enemies that come from behind is useful during the stages, its shortcomings tend to leave one side of your character vulnerable during boss fights. For stationary bosses, fixing your options in the direction of the boss is a decent solution, but there are times when you'll want to be shooting at an enemy while simultaneously retreating from it.

Take, for example, the centipede-like boss of Level 2, which moves faster than you and can appear from any one of six holes around the edges of the screen. As you pull away, your character turns around, leaving it up to your options to carry on the fight if they happen to be pointed that way at the moment. The character's inflexible shape does not lend itself well to maneuverability, so the fight doesn't feel fun or intuitive. Just an obligation.

Something about the way it looks to have a human floating along like a spaceship rings false with my cynical senses. Since there is no discernable jetpack on the characters' backs, it appears they have no reason to move in the manner they do, and what am I supposed to think when they end up in space without so much as a helmet?

... ...

If there is one exceptional aspect to S.C.A.T., it's that the soundtrack is outstanding. Natsume once again tapped the talents of former Konami composer Kyouhei Sada, just as they did for Abadox, and this is some of the best work I've heard from him yet. The score sounds like a direct cross between The Adventures of Bayou Billy, utilizing the same picked guitar effect, and Abadox's moodier, melodic parts. There's also a little bit of Contra sneaked in with the battleship stage's military-themed styling. Graphically, the game is competent, but aside from the lightning flashes amongst the bombed-out skyscrapers in Level 1 and possibly the final boss, there's nothing too impressive. In fact, the rapid scrolling of the elevator stage is so headache-inducing that I had to turn that background layer off when I played Final Mission emulated.

If my review comes across a little unfocused and disjointed, like I'm complaining about S.C.A.T.'s lack of challenge while simultaneously about the things that make it difficult...Well, I feel like that's the game that's been presented to me. One whose innovations feel more like reasons why other shooters are not done this way. One that, perhaps, needed something more to make it really work, but certainly not the six nerf balls Natsume threw at it.

... ...

The way it was released, S.C.A.T. is not enough of a game to give a strong recommendation to. I can definitely say it's not worth the exorbitantly high ebay prices for the cartridge, and whether or not it's worth purchasing on Wii Virtual Console depends if you feel $5 is fair for two (albeit lengthy) stages of challenge. But if you did buy it, emulation at least provides the option to play a harder version, like free DLC, which I recommend doing if you plan to get more out of the concept.

OVERALL

SCORE: 3/5

BACK TO NES

REVIEWS BACK TO MAIN

PAGE

|