... ... As a medium that relies highly on its visuals and audio, video games have, from almost the very beginning, begged to be compared to movies. The main difference, after all, is the requirement of input from the observer - a detail that often stands between video games and one's belief if they can be art or not. Long before any such discussions gained worldwide attention, there were visionaries who pioneered video games' ability to be a viable cinematic force. Maniac Mansion, in 1987, showed that the characters who populate a game's world can have personalities and thus participate in a narrative. A year later, Ninja Gaiden would prove that adding colorful cutscenes between stages could tell an ongoing story outside of the manual, which gave players an added level of motivation for completing the game: to see what comes next and how it eventually ends. 1991's Another World took this concept even farther by essentially being one really long, playable cutscene.

As a medium that relies highly on its visuals and audio, video games have, from almost the very beginning, begged to be compared to movies. The main difference, after all, is the requirement of input from the observer - a detail that often stands between video games and one's belief if they can be art or not. Long before any such discussions gained worldwide attention, there were visionaries who pioneered video games' ability to be a viable cinematic force. Maniac Mansion, in 1987, showed that the characters who populate a game's world can have personalities and thus participate in a narrative. A year later, Ninja Gaiden would prove that adding colorful cutscenes between stages could tell an ongoing story outside of the manual, which gave players an added level of motivation for completing the game: to see what comes next and how it eventually ends. 1991's Another World took this concept even farther by essentially being one really long, playable cutscene.

... ...

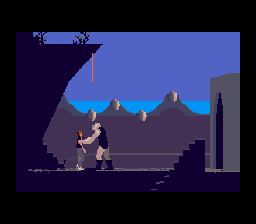

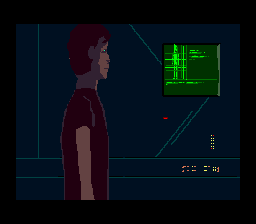

Originally created for the Amiga by Eric Chahi of French game developer, Delphine Software, Another World makes extensive use of polygons and rotoscoping to create lifelike characters and animations. Due to the technology limitations of the time, this approach would require the level of detail in objects and backgrounds to be stripped to a mininum, which may not have worked if not for the decision to place the game's events on a fantastically weird alien planet, and for the attention paid to the visual style.

... ...

Another World's fully-animated, opening cinema was certainly one of the longest and most indulgent seen in any game to that point. The speeding Ferrari of young physicist Lester Knight Chaykin (who curiously resembles Chahi) careens into a parking lot. The camera provides a closeup of his tennis shoes as he walks via elegant rotoscoped animation into an elevator and takes it down to a basement lab. Once there, he manipulates a computer that is so advanced, it seems to have no monitor, but rather projects its information into the space in front of Lester like an interactive hologram. As his experiment with a particle accelerator gets underway, a gathering storm outside sends a bolt of lightning into the lab. It causes an explosion so tremendous, that once where there was Lester and his desk, there is now only a gaping hole. If not for its (necessary) minimal use of color, this entire spectacle would look like something you should be watching on your TV without a game system hooked up to it.

... ...

Lester's story would seem the stuff of wish fulfillment, except that the situations he finds himself in as a result of his failed experiment are anything but admirable, and could even be described as "downright terrifying". His desk is teleported into a pool on a bleak alien planet. After swimming for his life and coming under attack by several hostile creatures (slimy tentacles, leeches, and something resembling a bear), Lester immediately finds himself a prisoner of the tall, buff humanoid figures that comprise the planet's ruling society.

... ...

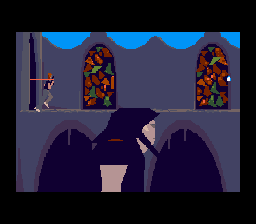

Upon breaking free of an incompetently-crafted prison cage, Lester engages in a neverending life-or-death struggle to escape from the alien overseers. The odds are tipped ever-so-slightly in his favor by the acquisition of a strange gun that has both defensive and offensive capabilities, and the helping hand of his grateful cellmate (known in the fandom as "Buddy") who was also freed during Lester's escape. Buddy will show up at key points in the game to "deus ex machina" Lester out of otherwise hopeless situations.

... ...

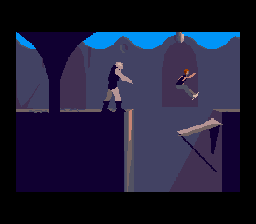

The only time Lester receives a respite from being chased is when he is confronted with an obstacle that bars his progress. In these situations, Lester will need more than just his gun and Buddy - he will need the player's brain power to help him solve puzzles and platforming skills to leap pits and chasms.

... ...

Finding the way forward often involves traversing some of the darkest, most claustrophobic and hellish caverns seen in a 2D game since the bizarre underworld of A Boy and His Blob (an earlier forefather of this genre), or the heavily-guarded hallways of a lavish palace. The creepiness of the environments is augmented by the obscuring colors (an eerily quiet pool with a single lamp above it beckons you to plunge into its unknown abyss). The tension is built by the sparse, but effective soundtrack. An electronic pulse argues with a flute until Lester needs to run for his life, at which point some of the most hectic chase music in game history urges him on.

... ...

Since the story is told with a complete lack of dialogue, the only means by which we gain any empathy for Lester is through his lifelike motions. We feel for him because he behaves like we do. His character sprite would be a ghastly array of pixels, if not for how fluidly animated he is - he responds to his surroundings in particular ways. Previous video game heroes had specific animation frames for walking, running (which was usually just the walking animation sped up), jumping, attacking, and dying... and perhaps for climbing a ladder or walking up a flight of stairs.

... ...

Lester not only has all of these, beefed up significantly from the 2-3 frames of his contemporaries, but he also has very specific animations for very specific situations. No matter what enemy Mario is defeated by, he will always die the same way. Lester may be dragged down by his feet into the chomping maw of a miniature Sarlacc pit, or impaled on a bed of spikes, or vaporized by a laser beam, or roll over and "turtleshell" as he is mauled by the alien guards. Drowning deaths have their own cinema.

... ...

Since Another World's critical and commercial success guaranteed it would be ported to a number of computers and consoles, that it would come to Nintendo's flourishing 16-bit system was inevitable. When Interplay published it in the USA, it was renamed to "Out of This World" because there existed a TV show called "Another World"...which is ironic since there was also another TV show called "Out of This World"... Interplay just couldn't catch a break, I suppose.

... ...

Though the SNES version does suffer a little from slowdown (no doubt it was pushing the console's processing power quite a bit - this was before the era of the Super FX chip that would make polygonal graphics a breeze for it to handle), it is, perhaps ironically, still my favorite version of the game of those I've played. This is largely because of the soundtrack, which is mostly unique to the SNES port. The Sega Genesis version does contain some, but not all, of the music, and has even worse slowdown, if that can be believed.

... ...

There is, however, one problem that players attuned to SNES games in 1992 were probably not expecting, and that is the game's brevity. Some early SNES launch titles (Super Mario World, ActRaiser, Super Castlevania IV) have received criticism for being short, but if Out of This World takes longer to complete, it's only because it's far less forgiving with its checkpoints. Lester will die and die often, usually requiring lengthy scenarios to be redone multiple times. It's also likely that before you hit on the right solution to some puzzles, you will make the wrong moves several times, which will force you to kill Lester on purpose and start over again from the last checkpoint. The only game I know of that is stingier with its passwords is King Arthur & the Knights of Justice. I would not necessarily say this is a bad thing, as some modern remakes are so generous with checkpoints, the game becomes pointlessly easy.

... ...

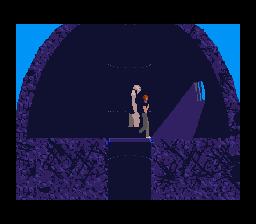

Out of This World's lack of length is not without reason. Eric Chahi admits to having made up the story as it went along, and he seems to have written Lester into a situation that he couldn't be written out of. (He would later express regrets about telling the sequel's developers that Lester should die in it.) The game feels like it has no third act, or rather a third act that's ridiculously shorter and easier than anything before it since the first act. It starts with a bizarre arena sequence where Lester and Buddy have to be ejected from a tank. To this day, I have no idea what the "real" solution to that part is, I simply press buttons until the game advances. From then out out, it's just "outrun the guards", which is not without its challenges, but is nothing you haven't done before. Cutscenes advancing the plot have become more scarce at this point, and the ending, despite some nice cinematic graphics and music, doesn't feel like one.

... ...

While I felt cheated by that ending back in the 90s, these days I'm more appreciative of the other goals Out of This World had achieved. It was proof that video games could be more like movies while still maintaining thoughtful and innovative challenges. Considering he has not a single line of dialogue, I realized that the fact that I cared about what happened to Lester at all indicated the impression that the rest of the game had made on me.

SCORE: 3.5/5

BACK TO GAME

REVIEWS

BACK

TO MAIN PAGE

|